The role that monitoring, evaluation and learning (MEL) practitioners play has always been different in market system development (MSD) programs. As the field of MSD evolves, so does the role of the MEL specialist, as MEL becomes even more central to delivering on our inclusive systems change ambitions.

For years, the competencies of an effective MEL professional in international development included being able to set up and carry out reliable data management processes to measure progress on indicators. There is no doubt of the need for donors to have proof that they are getting value for money, but the function of MEL in MSD programming has required more.

To rise to the challenge of MEL in a modern-day MSD program, there are three core areas where MEL specialists should focus their attention:

- Focus more intentionally on learning to improve programming and transform systems themselves;

- Supporting initial diagnoses of systems, development of change strategies, and setting up a systems-informed monitoring plan; and

- Assessing change over time and evolving systems change monitoring processes and program strategies.

Shifting the Locus of Learning

Beyond just proving and reporting — an additional and arguably more important competency needed in a modern MEL specialist is related to learning. This is because of the emphasis the MSD approach places on the facilitation of changes through local system actors that necessitates improved learning while doing. Learning by local system actors and the focus systems is core to achieving systemic change. Many have looked towards the DCED standard for guidance on how to do effective MEL in programming and refer to this as a need for an emphasis on data that helps “improve” not just “prove” what is working or not, in order to change how local system actors interact and ultimately how market systems function.

This increasing focus on learning demands a shift towards using data to drive improved outcomes by helping local system actors, like businesses, governments, and organizations collect and use data that fuels evidence-based decision-making during implementation.

System Change Diagnostics Into Strategy

MEL practitioners in MSD need to be able to focus on ensuring technical programming has effectively addressed the conditions that hold a systemic problem in place.

If the system has not been well assessed and leverage points that shape patterns and dynamics underlying challenges (be they poverty, migration, crime, and violence, etc.) have not been identified and influenced, then when the activity or program that stimulated the changes with local system actors ends, the market system may revert or even worsen.

Assessing Change Over Time and Adapting Assessment Processes and Program Strategies

But the challenge is that those conditions change over time. If we do not update our understanding through monitoring, we will miss important signals that something might not be working. Moreover, we may become too biased by our own theories or ideas that we overlook contradictory signals.

- How can we navigate this uncertain terrain without a compass that tells us when we are veering off track?

- If assessment is relegated only to the beginning and end of a program, then how can we make effective decisions in between?

Not being able to assess systems change effectively can thwart innovation and exacerbate the challenges international development seeks to address.

So, if assessing systems change is so important to the sustainability and impact of programming, especially in MSD, MEL practitioners not only need to know how to do it — but to do it well.

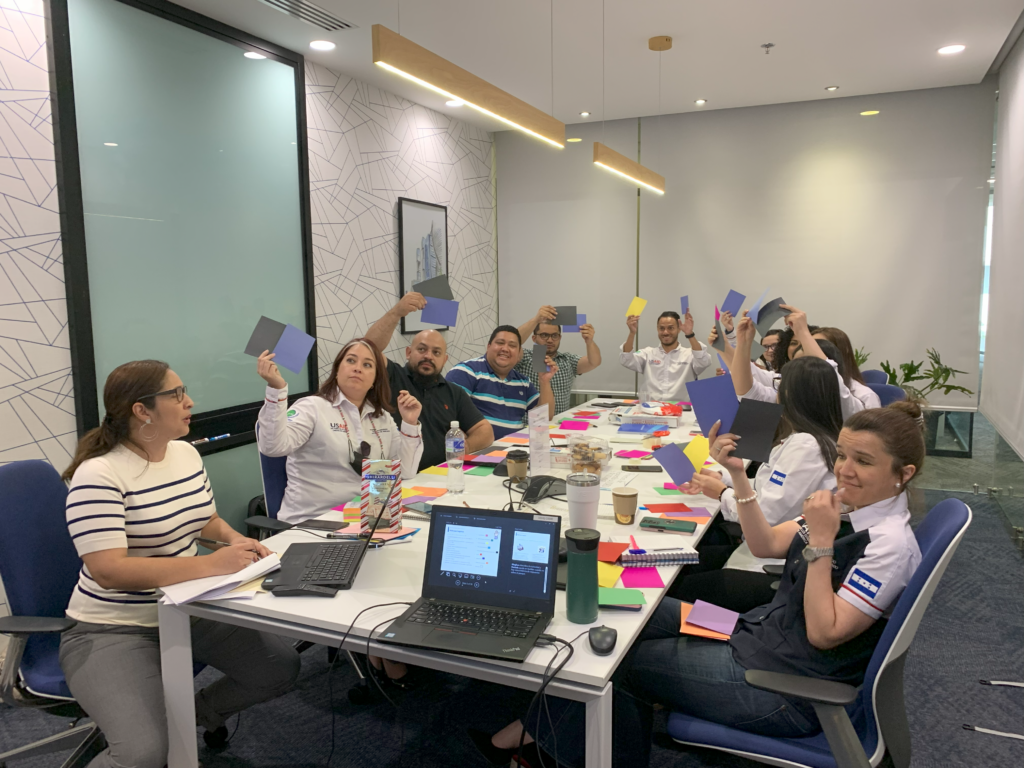

This is why the MEL clinics that USAID facilitated through the Feed the Future Market Systems and Partnerships (MSP) Activity were so important in 2022. These clinics gathered MEL practitioners from various organizations working on MSD programming to come together and discuss the challenges we have faced. We also supported each other to work through how we address such challenges and what other considerations we could or should keep in mind. This support led to the development of a “Practitioners Guidance to Assessing Systems Change.”

The guidance covers four key parts of assessing systems change: 1) bounding the system, 2) defining outcomes, 3️) assessing degrees of changes and 4) establishing contribution. It also includes practical tips, rubrics, templates, analysis frameworks and exercises. (You can hear me and my fellow co-authors from around the world share our favorite parts in this 3-minute video).

Reassessing the Role of a MEL Specialist

The challenge that MEL staff on MSD programming have, though, goes beyond delivering on these three areas above. Data, for example, do not automatically impact program decisions. The biggest hurdle, in my opinion, is in discovering how to transform the role or function that MEL plays in programming both within an international development activity and with local system partners. To do this, we need to think about internal decision-making processes and power dynamics WITHIN the project! And, critically, the role of the MEL Manager.

MEL should not be seen as the clean-up crew that follows interventions and systems dynamics, trying to just make sense of the messiness after the fact and reporting back to other technical specialists, program leadership and donors. Rather, MEL should be a facilitative force not just in sharing feedback, but a force that helps stimulate and co-create intervention design with learning while doing in mind. As another group in the MEL clinics discussed, MEL Specialists are often overlooked potential agents of change in a Team Leader/Chief of Party’s efforts to cultivate the culture needed to implement an MSD approach, such as through cultivating journalistic inquiry that supports critical and leveraging insights on early signs of change to build staff buy-in to stay the course for an MSD approach.

A MEL Specialist Role Model

Recently, Harieth Marisol Nuñez, MEL Director on the USAID Honduras Transforming Market Systems (TMS) Activity, was recognized for doing just that. She was presenting to an external leadership team during a portfolio review on how TMS has intentionally worked differently than other international development programs to understand and assess the Honduran market system. She could articulate how TMS identified the root causes and factors that have created self-perpetuating cycles that encourage migration from Honduras. She could explain how the factors are monitored by the Universidad Nacional Autonoma de Honduras (UNAH, the largest and highly ranked university in Honduras) by consulting local businesses and organizations about the influence and dependence of factors on the problems the activity seeks to address.

But, even more so, she could explain how the participatory process of collaborating, learning, and adapting (CLA) to transform the challenges that local partners working with TMS confront into opportunities for innovation and learning are at the heart of the TMS MEL system. She showed dashboards with data that local partners use to track new jobs created and improved income, as well as how they use this and other data in the MEL system to reflect on feedback.

Feedback is an important systems concept to consider where there are indications that there may be traction for innovation (reinforcing the change) versus where there might be pushback in the system that could thwart it (balancing feedback).

As part of this review, a seasoned member of the leadership team responded with, “I don’t think I’ve heard another MEL officer speak that way before.” This not only made some of the co-authors of the Practitioners Guidance to Assessing Systems Change and colleagues of Nuñez proud of how she drives change but also of how the changing role of MEL is noticeable.

When MEL has a voice not just after the fact, but upfront, in detecting and articulating what is happening in a system from research, especially consultations with local system actors, decision-making on where there are leverage points for systems change improves.This also makes it easier for MEL to work alongside local system actors and technical staff in learning while making efforts to stimulate changes in system dynamics. MEL can and should help teams identify where there is traction for change and not, so that pivots can be made iteratively as MEL assesses and shares feedback. Setting up the processes and culture that enable MEL to be and do more than before is key.

MEL provides insights to not only activity staff, but also partners, that flag where there are indications of systemic change. Not all MEL specialists are alike, of course, and some are better positioned to respond to today’s demands better than others. The text box offers four areas I and other colleagues have observed are critical areas of which the MEL in MSD community needs more.

What a MEL Manager in MSD Needs

- More of a voice in intervention design with local actors and technical specialists to ensure learning while doing is intentional from the start;

- Support to engage in peer networks that are using systems thinking concepts and tools;

- Access to skill-building opportunities like conferences and training; and

- Access to practical resources (human and knowledge) to assess systemic change and what to do with assessments with local actors and technical specialists.

MEL practitioners need to have the know-how not only to detect but also assess how much change is occurring and to work with others to contribute to more inclusive market systems that benefit the vulnerable.

I, for one, know that this is one of my motivations to work in systemic change measurement and to promote and amplify where MEL practitioners can — and do— facilitate change.

This blog was authored by Meghan Bolden and was originally published on AgriLinks.

Meghan also co-authored the Practitioners Guidance to Assessing Systems Change blog and additional papers focused on the role of MEL Managers in building a team culture that supports MSD and tips from MEL Managers on enhancing partner and system-level learning.